Web services and IFTTT

Cybersecurity First Principles in this lesson

-

Abstraction: An abstraction is a representation of an object or concept. It could be something such as a door, a speedometer, or a data structure in computer science. Abstraction decouples the design from the implementation. The gauges in an automobile are an abstraction of the performance of a car. A map is an abstraction of the earth.

-

Data Hiding: Data hiding is the technique that does not allow certain aspects of an object to be observed or accessed. Data and information hiding keeps the programmer from having complete access to data structures. It allows access to only what is necessary.

-

Minimization: Minimization refers to having the least functionality necessary in a program or device. The goal of minimization is to simplify and decrease the number of ways that software can be exploited. This can include turning off ports that are not needed, reducing the amount of code running on a machine, and/or turning off unneeded features in an application.

-

Modularization: The concept of modularity is like building blocks. Each block (or module) can be put in or taken out from a bigger project. Each module has its own separate function that is interchangeable with other modules.

-

Resource Encapsulation: Encapsulation is an object oriented concept where all data and functions required to use the resource are packaged into a single self-contained component. The goal is to only allow access or manipulation of the resource in the way the designer intended. An example, assume a flag pole is the object. There are fixed methods on how the flag pole is to be used. Put the flag on, take the flag off, raise or lower the flag. Nothing else can be done to the flag pole.

Introduction and goals

In this lesson, we will learn how to plug and play different web services together to make some simple inventions that can automate tasks and send alerts, alarms, and messages based on various triggers.

Goals

By the end of this tutorial, you will be able to:

- Interact with

web services Mashupweb services to make some apps that automate tasks

Materials Required

- A free IFTTT Account (instructions to create one in this lesson)

Prerequisite lessons

Table of Contents

- [Cybersecurity First Principles in this lesson](#cybersecurity-first-principles-in-this-lesson)

- [Introduction and goals](#introduction-and-goals)

- [Goals](#goals)

- [Materials Required](#materials-required)

- [Prerequisite lessons](#prerequisite-lessons)

- [Table of Contents](#table-of-contents)

- [Before We Start](#before-we-start)

- [Using web services](#using-web-services)

- [Create an IFTTT Account](#create-an-ifttt-account)

- [Everything is an applet](#everything-is-an-applet)

- [Web Service Wizardry - your first applet](#web-service-wizardry---your-first-applet)

- [Email a tweet](#email-a-tweet)

- [Maker service to a Tweet](#maker-service-to-a-tweet)

- [Self Exploration](#self-exploration)

- [Cybersecurity First Principle Reflections](#cybersecurity-first-principle-reflections)

- [Lead Author](#lead-author)

- [Acknowledgements](#acknowledgements)

- [License](#license) <!-- TOC END -->

Before We Start

In the computational thinking lesson, you learned how to think systematically about a problem, discover the needs of problem stakeholders, design a solution, and test it. You will put those skills to work here.

Using web services

Web services are, as the name implies, services that live on the web. You use these all the time - mostly without knowing it. The internet is built on top of them. Google, Dropbox, Youtube, Twitter, and Facebook are just a few juggernauts that provide and use many different web services. In this lesson, we are going to use a mashup service called IFTTT (which stands for If This, Then That ). IFTTT is a great platform that talks to all kinds of other web services. This is a great example of the modularity cybersecurity first principle, because IFTTT can swap out components for others easily.

Create an IFTTT Account

To start we need to create an account:

- Visit https://ifttt.com

- You will need to create an account with

IFTTTif you don’t already have one. Clickget startedto make an account - Walk through the online instructions to create your account

Everything is an applet

Once you sign in, you will see might see some recipes that have already been made for you by the IFTTT team. A recipe is a design pattern that combines input and output behavior to do something cool. IFTTT refers to recipes as applets.

In IFTTT, everything you might want to do involves making an applet. An applet in IFTTT is a very simple app that involves two services. The basic premise is that if something happens in an input service (we will call it service A), then an output service (aka service B) should do something using its capabilities in response. Applets allow you to mix and match services as inputs and outputs in a similar way to how GPIO pins allow for different components to work together on the same interface. This is an example of modularity. The applet concept also encapsulates the service resource. This is a nice example of resource encapsulation because you don’t need to know how the service works or why, just that it accepts certain inputs/outputs and performs a certain kind of task.

Web Service Wizardry - your first applet

Let’s create a new applet that sends an email whenever an IFTTT trigger receives an email. This applet only uses one service - an email service, but uses two different features of the service.

- In your browser, visit https://ifttt.com/create or go to https://ifttt.com/home and click

create +. - Click the

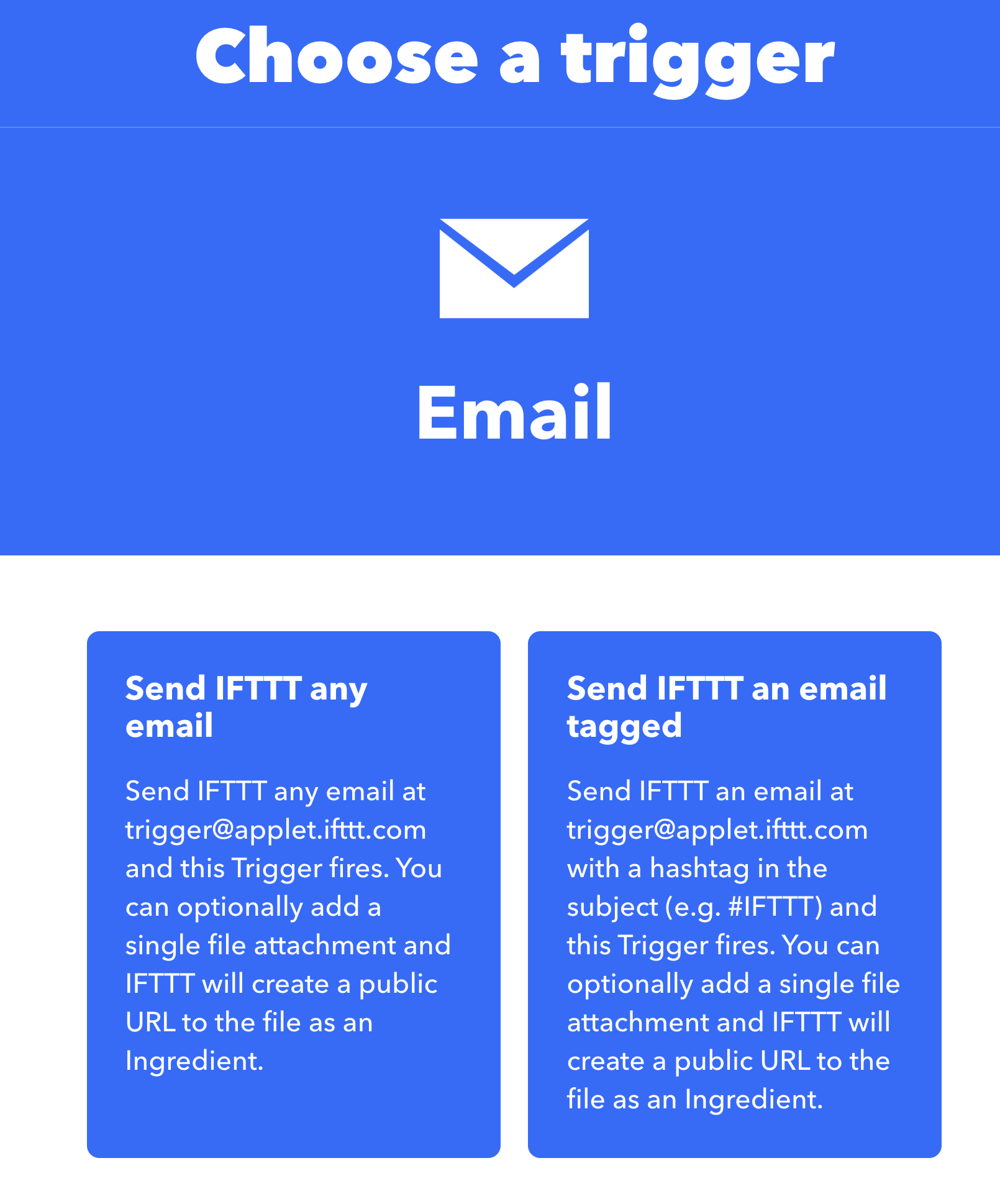

addbutton to specify the IF condition our applet will fire up on. - You will see all of the service options available to be used as IF conditions. Find

emailby typing it in the search/filter bar. - Select the first option

Send IFTTTany email.

- Now click the

addicon to specify the THAT condition. - You will again see all of the service options, select

emailagain and then send me an email. You will be asked to link your email to yourIFTTTaccount (if you haven’t already). Go ahead and confirm your email. - Once selected, you will see an email template available. Click

add ingredientto see available information coming from the input. You should have,from,bodyand other options that come from the input service. You can customize the email message here if you want. - When satisfied, select create action to set the email service as the THAT.

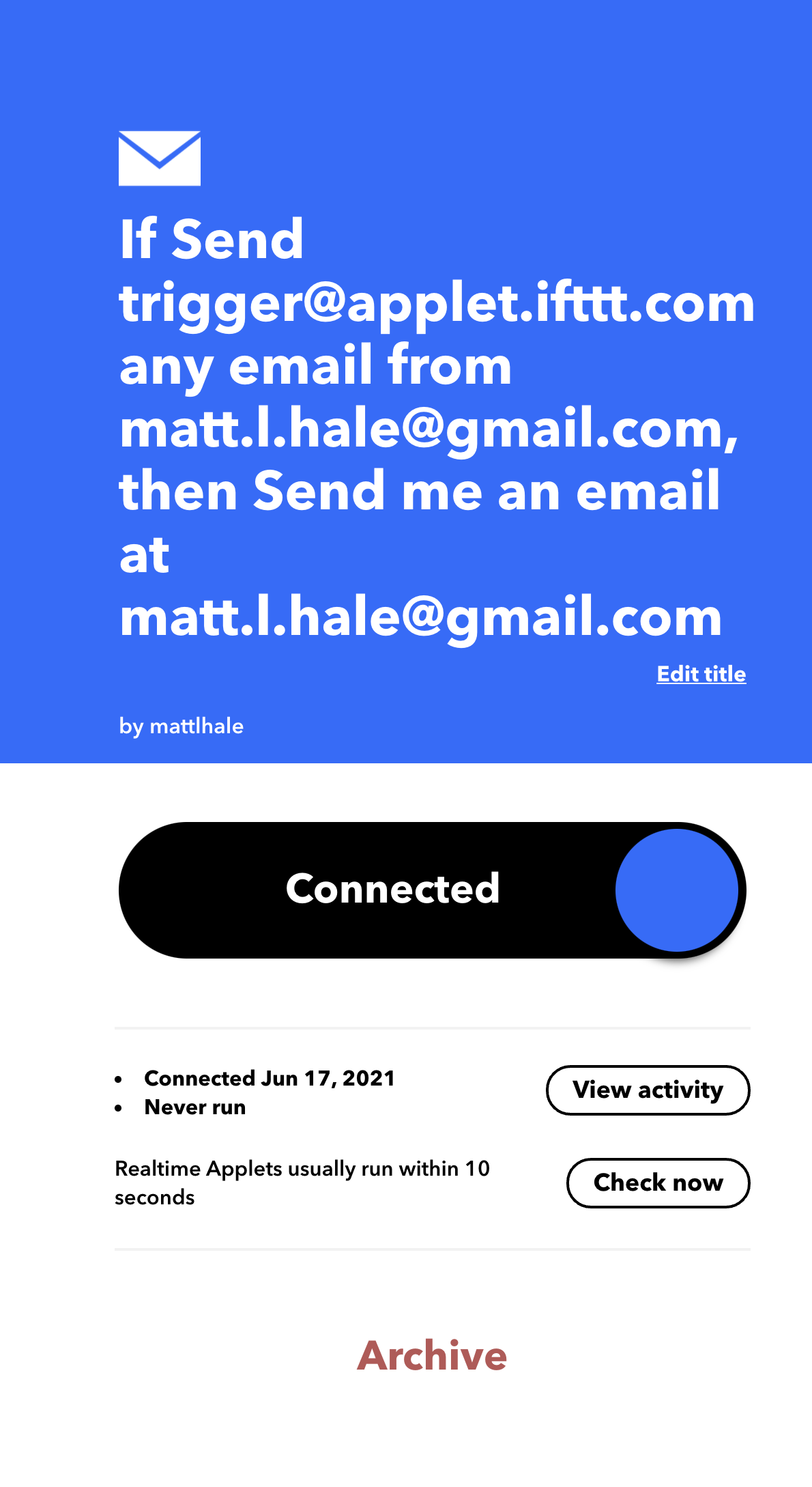

- Click continue and then finish to turn the applet on.

- You should see the applet as a box explaining what it does.

- Try it out by emailing

trigger@applet.ifttt.com

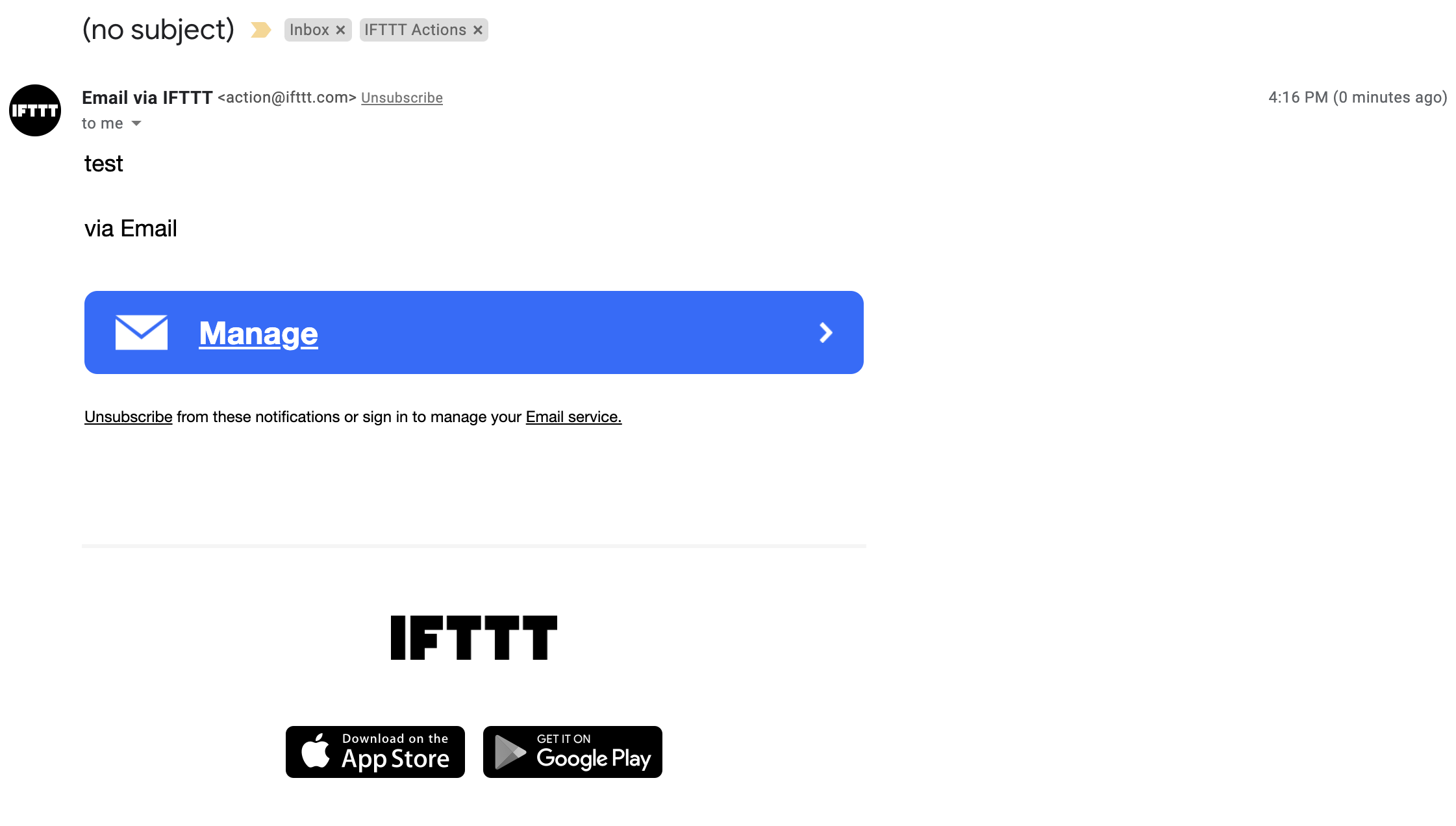

Check your email!

It worked!

This is a simple, but powerful tool. It also shows off resource encapsulation and abstraction. In terms of resource encapsulation, each of the services connected to IFTTT have many functions. These functions are encapsulated in a service (e.g. email in this example). The functions are also abstract because IFTTT doesn’t need to know how they work, just that they achieve a certain purpose (e.g. send an email). This helps model or abstract the implementation away from the design.

Email a tweet

Let’s make an app that accepts an email and then sends a tweet. This requires a Twitter account. If you don’t have and don’t want to create a Twitter account, feel free to skip this, but it’s fun!

- Go to https://ifttt.com/home, click Create+.

- As the IF condition, select

emailonce again. - This time, select the

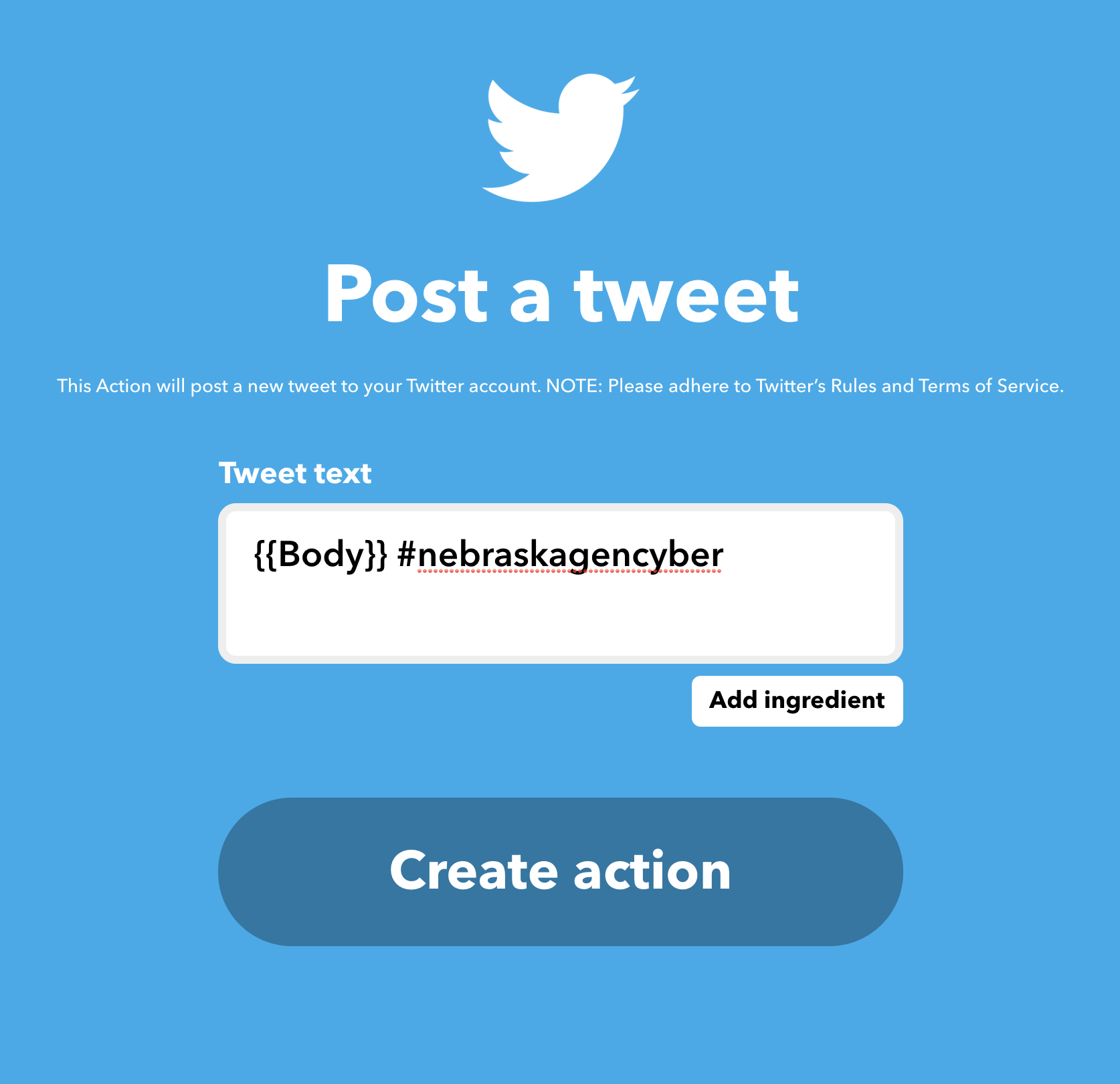

Send IFTTT an email taggedoption - Give it the hashtag

nebraskagencyber - For the THAT service, select the

Twitterservice. You will be asked to link your Twitter account first. - Select the

Post a Tweetoption. - Make your tweet text as follows:

- Press create action and then finish

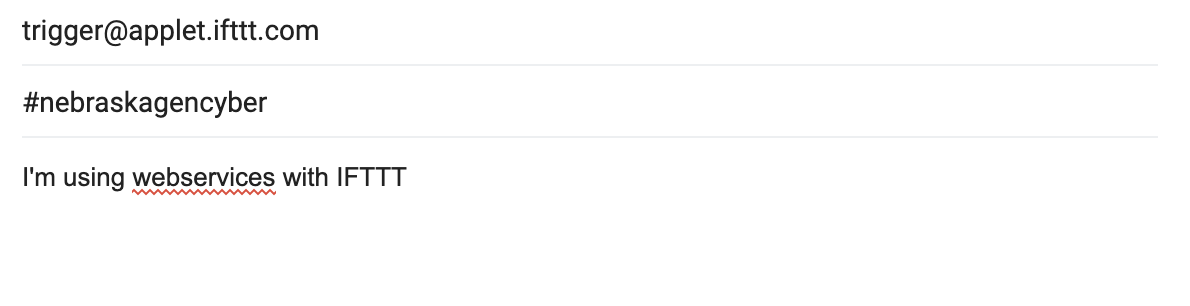

Now let’s try it out. Send an email to trigger@applet.ifttt.com

Make sure to include the #nebraskagencyber in the subject line. Then for the message put whatever you want to appear in your tweet. For mine, I went with the following:

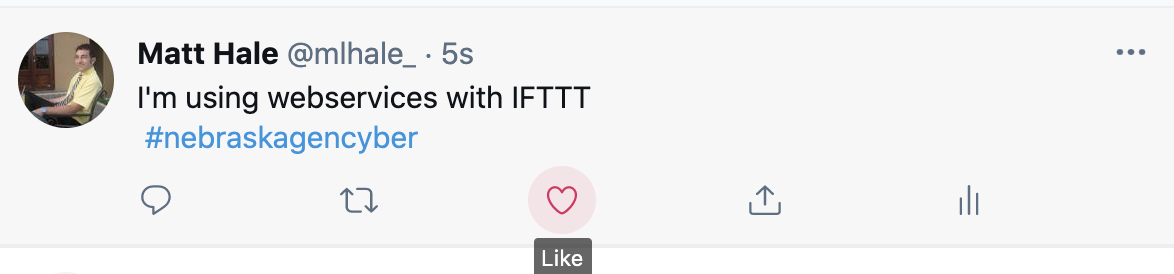

This posted to twitter for me:

Pretty neat!

Maker service to a Tweet

In IFTTT there is a special service called a webhook that allows makers (like you!) to trigger events programmatically and pass them data. Lets experiment create an applet that sends a tweet using a webhook.

- Go to https://ifttt.com/home, click Create+.

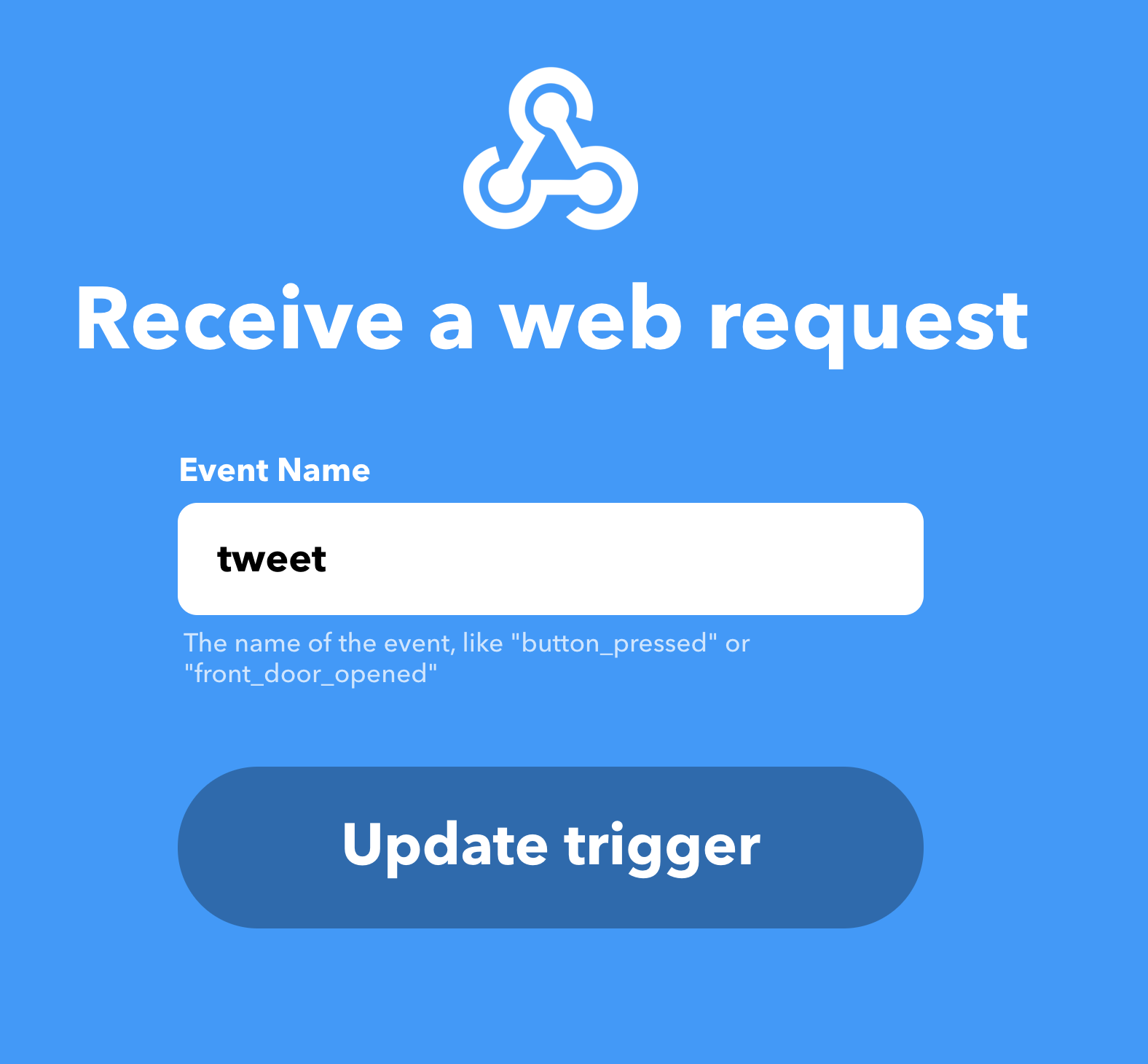

- As the IF condition, select

webhooksas the service A. - A webhook requires an event name. Let’s call ours

tweet.

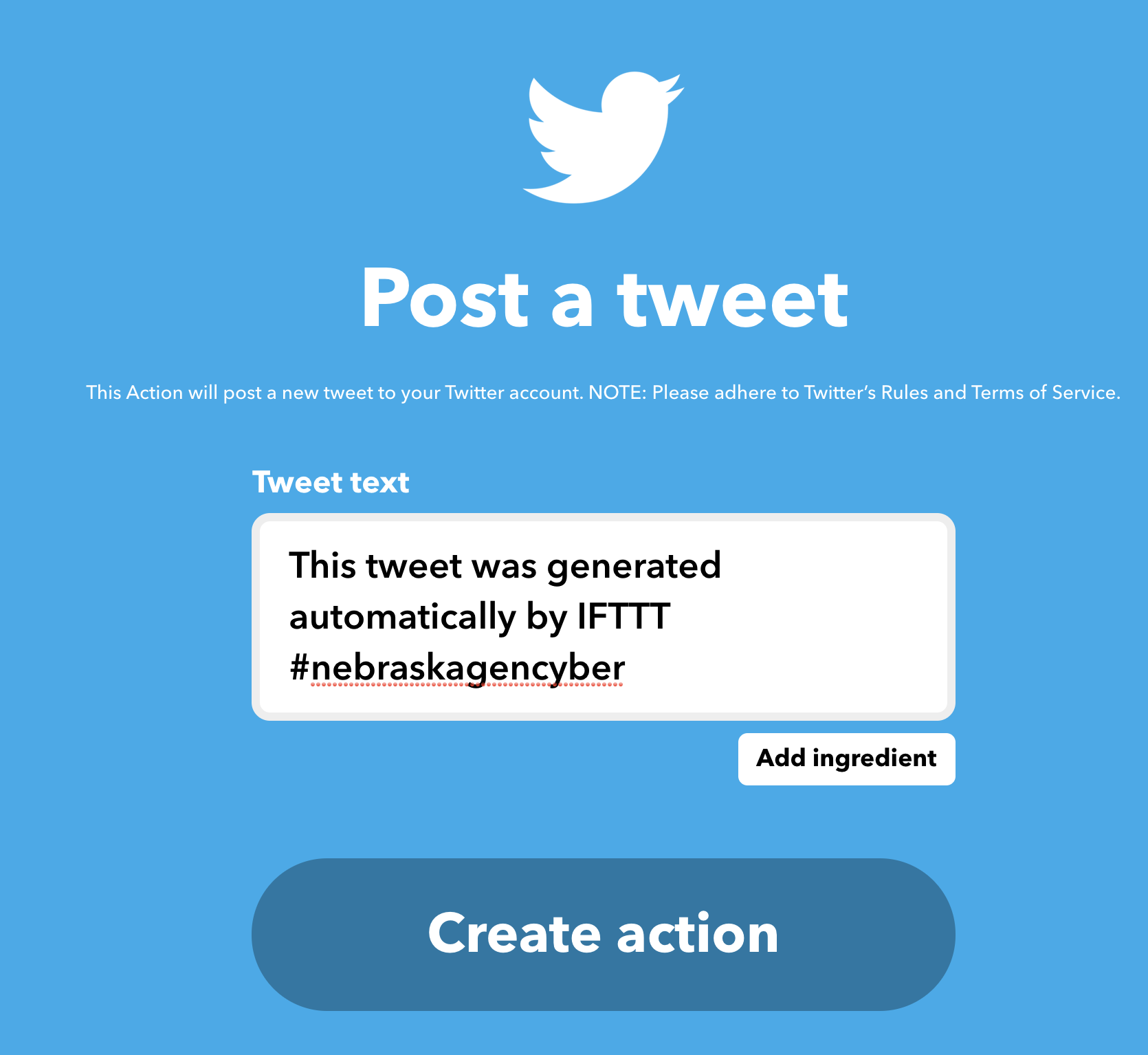

- For the THAT service, select

twitteronce again. - Configure your

post a tweetoption to look like this:

- Press create action and then finish

Now, triggering our maker webhook requires us to know a little bit about how this service works. Since it is not fully specified, it allows us to develop our own behaviors. For our tweet applet, we need to send the tweet event to maker service.

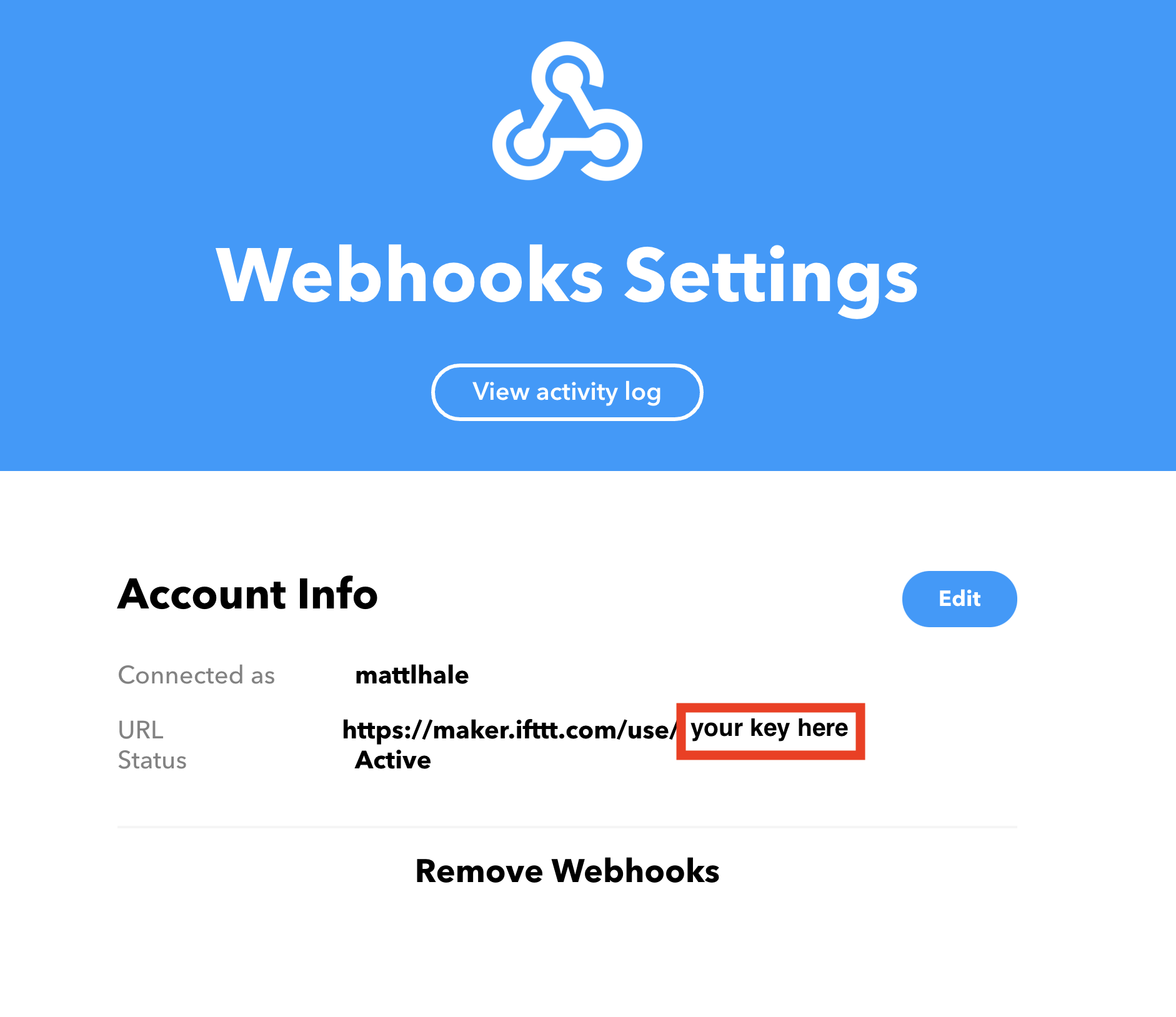

To figure out how we do that, visit this page: https://ifttt.com/maker_webhooks/settings

Here you will see the name of your account and the url that you can use to learn more about how the maker (webhook) service works.

Note the area outlined in red. This is something called your secret key. It is a unique secret just for you. Don’t share it! A secret key is kind of a like a password that programs uses to interface with other programs (like the service-to-service interactions we’ve been making with IFTTT).

If you want to visit the link shown there, you will get some detailed information about how this service works. This kind of information is called Service Documentation and can be used to execute the service.

In our tweet applet, we need to trigger an event called tweet. The service documentation tells us that the correct way to do so is to send a url request to the endpoint below:

https://maker.ifttt.com/trigger/tweet/with/key/your_key_goes_here

The documentation also tells us we can send parameters labeled Value1 to Value3. For our applet, we won’t need these right now, but keep this in mind - because later lessons will use these.

For now, visit the link above in a browser after you’ve inserted your own secret key into the url.

You have just connected one component (a browser) to a programmatic interface service and finally onward to twitter. Let’s check the result. You should see this in your browser:

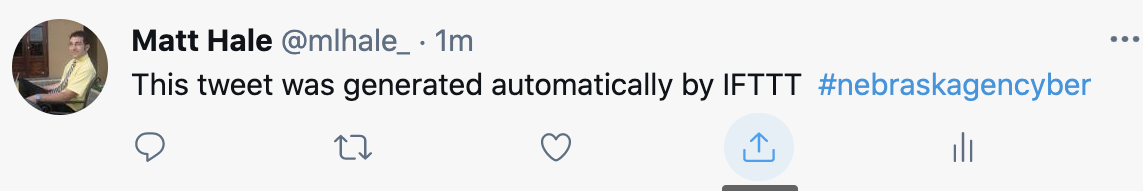

And this on twitter:

Well done!

Self Exploration

Try some different designs yourself. You can combine any services with any other services. You could also change out some of the ingredients in the patterns we used to try some other ones.

Cybersecurity First Principle Reflections

In this lesson, we saw web services, such as IFTTT, can abstract away details about devices and instead focus on recipes or design patterns to describe how things work. We also saw that by keeping functionality modular, IFTTT can combine many services together. We only need to know about input and output parameters to link them together.

Web services use resource encapsulation to ensure that all functions related to the execution of an app or service are neatly within the scope of the service itself. IFTTT relies on services to be encapsulated so that they can provide external services a simple interface to use their abilities.

Data hiding is also important to prevent internal data in the service from being released outside of the service invocation. Local data remains hidden, while interfaces expose only what the service wants to release (for instance to IFTTT). This also relates to minimization because services can turn ports and other access off except for the specific interfaces it wants to leave open for other services to use.

Lead Author

- Matt Hale

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to Dr. Robin Gandhi for reviewing and editing this lesson.

License

Nebraska GenCyber

is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Overall content: Copyright (C) 2017-2021 Dr. Matthew L. Hale, Dr. Robin Gandhi, and Dr. Briana B. Morrison.

Lesson content: Copyright (C) Dr. Matthew L. Hale 2021.

This lesson is licensed by the author under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.